What is PKD?

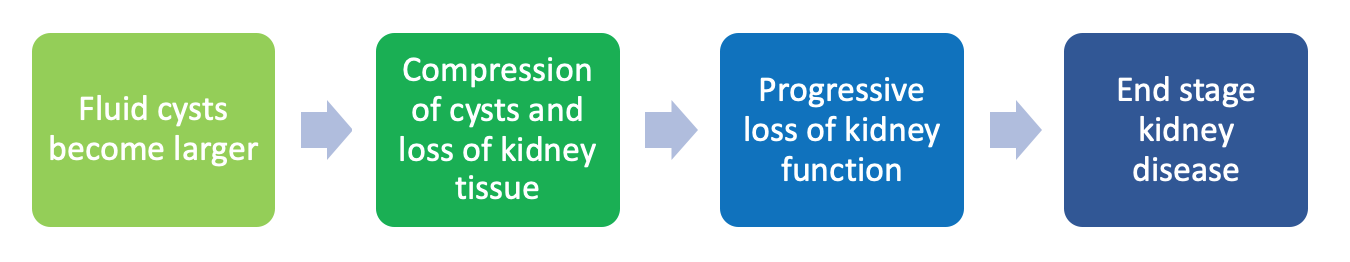

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is the most common inherited cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). PKD is characterized by the accumulation of many fluid-filled cysts on the kidney(s). Over time, the cysts get larger and larger and triggers a decline in kidney function. The cysts damage the kidney by blocking the flow of urine and causes inflammation. As PKD progresses, the kidneys gradually lose their ability to work effectively.

PKD can be either autosomal dominant or recessive. Autosomal dominant type of PKD is the more common of the two types of PKD.

- Autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) is identified by the development and progressive enlargement of fluid-filled renal cysts. If one parent has PKD, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

- Autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD) is a rare type of PKD but means both the mom and dad had the genetic mutation and passed the genetic mutation to the child by recessive inheritance.

Why do the fluid-filled cysts develop on the kidneys?

Impaired calcium regulation (a mineral) and elevated vasopressin levels (a hormone) lead to extra cells developing and fluid secretion which are the main reasons why cysts develop on the kidneys. Over time the fluid-filled cysts may get larger and larger causing the kidneys to become larger in size. The fluid-filled cysts damage the kidneys and this damage prevents the kidneys from working properly. The kidneys are then not able to do their jobs properly like filter the blood and remove wastes. Advancement of the disease can often go unnoticed because normal kidney function can hide the severity of disease progression until irreversible damage has already occurred. As the kidneys expand with more and more cysts, a person may experience increased pain to their flank (side). And this side pain may be what initiates that first call to a healthcare provider for an evaluation/exam.

*Important to note: The loss of kidney function is irreversible – once it is gone, it does not come back, even with medications and lifestyle changes.

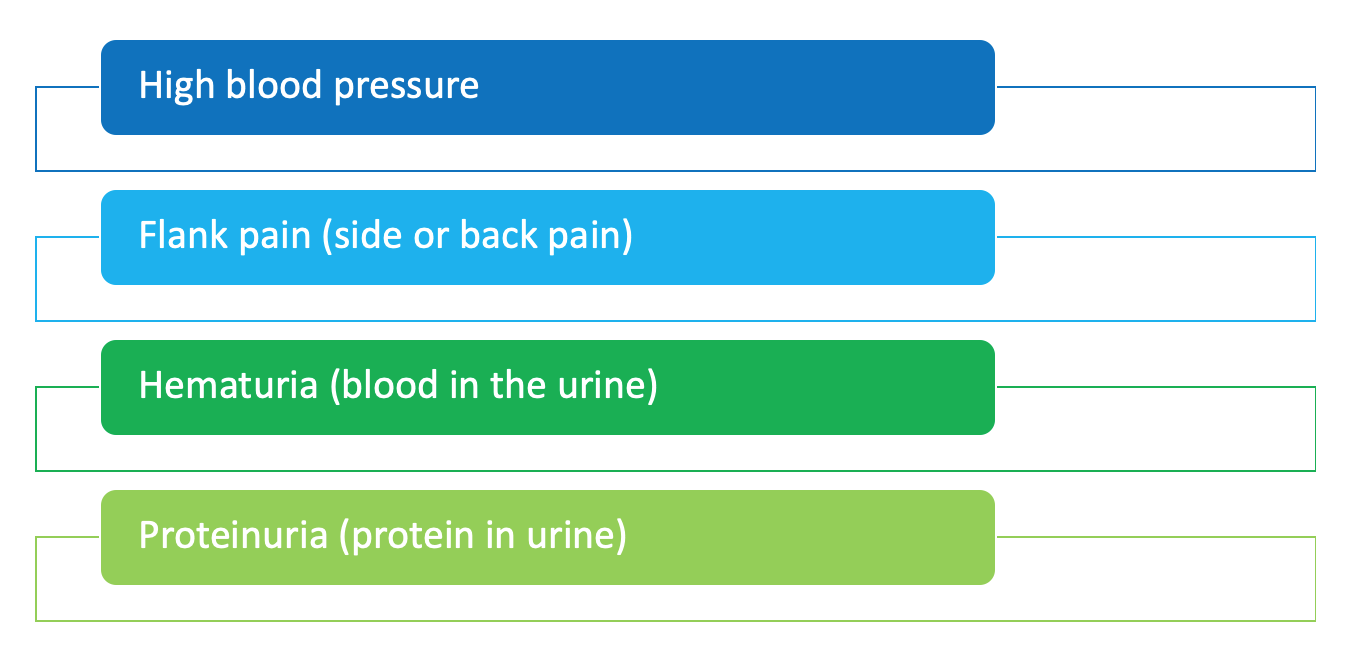

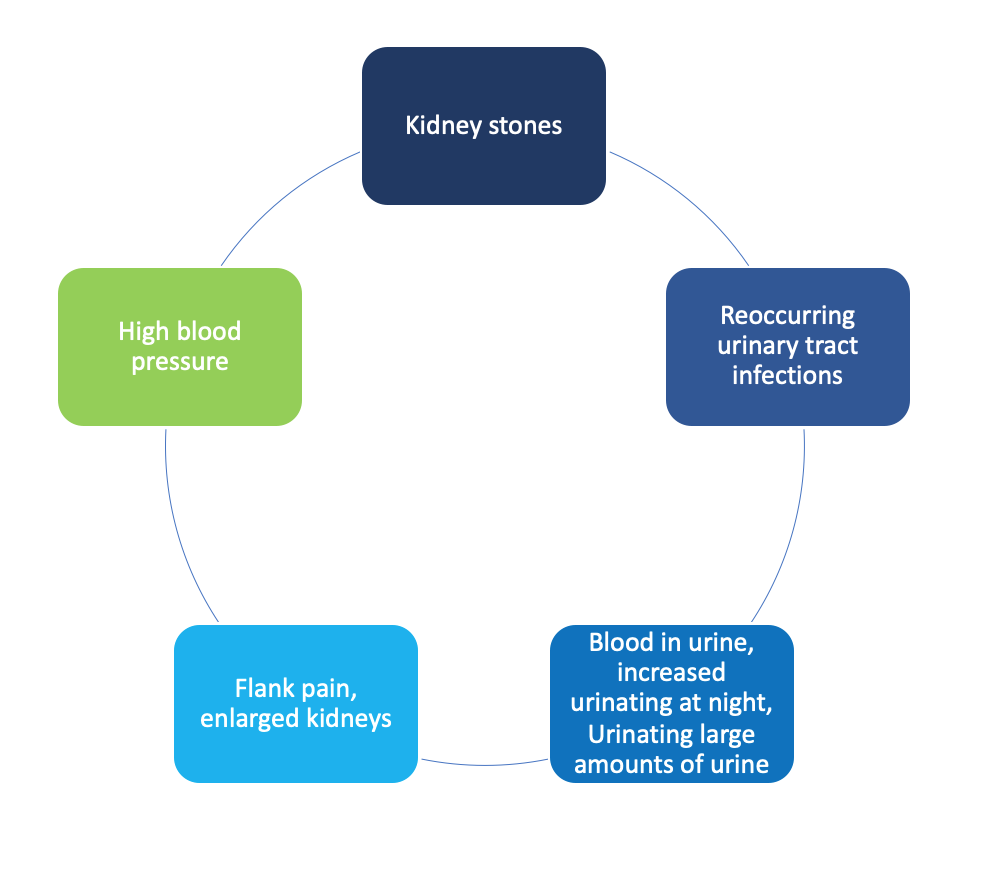

What are the symptoms of PKD?

As PKD is an inherited disorder, most families may already know if there is a risk for developing PKD. But, in some people, prior family history may not be known. Recognizing symptoms is extremely important especially early on because symptoms may not be easily noticeable. If you have any of the following signs and symptoms contact your healthcare provider:

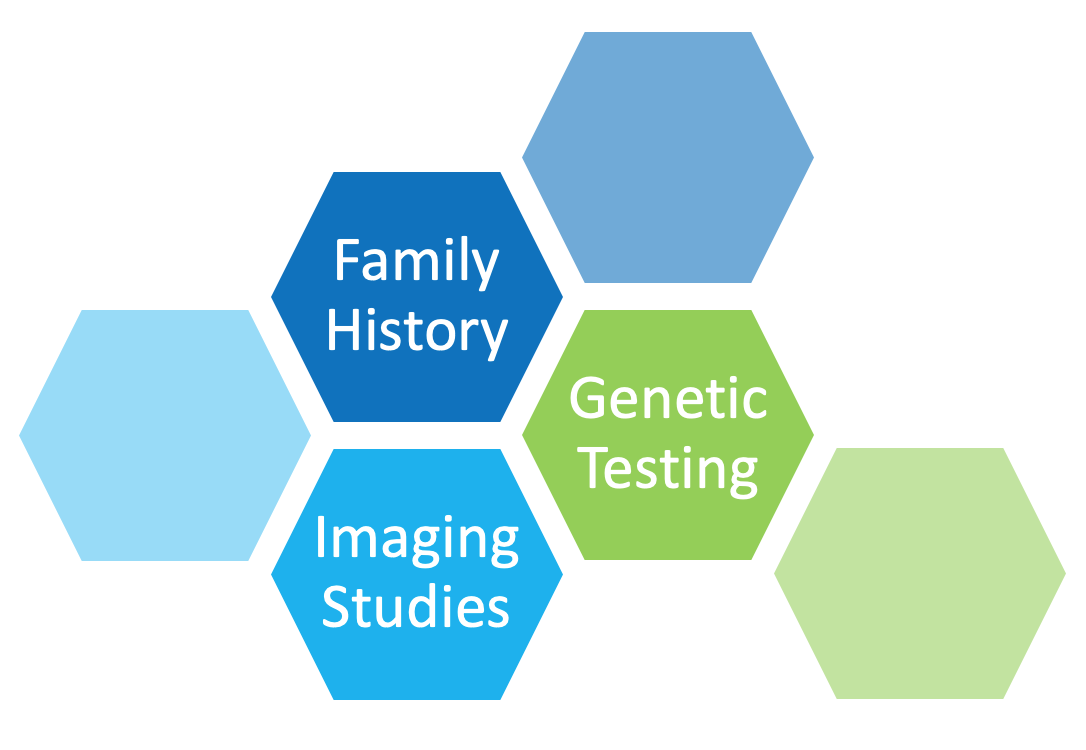

How is PKD diagnosed?

For people with a positive family history of PKD, early screening and genetic testing is available to help confirm a diagnosis.

If there is no family history of PKD, it may be hard to detect PKD because early symptoms may be vague. Regular health maintenance screenings with your healthcare team are important.

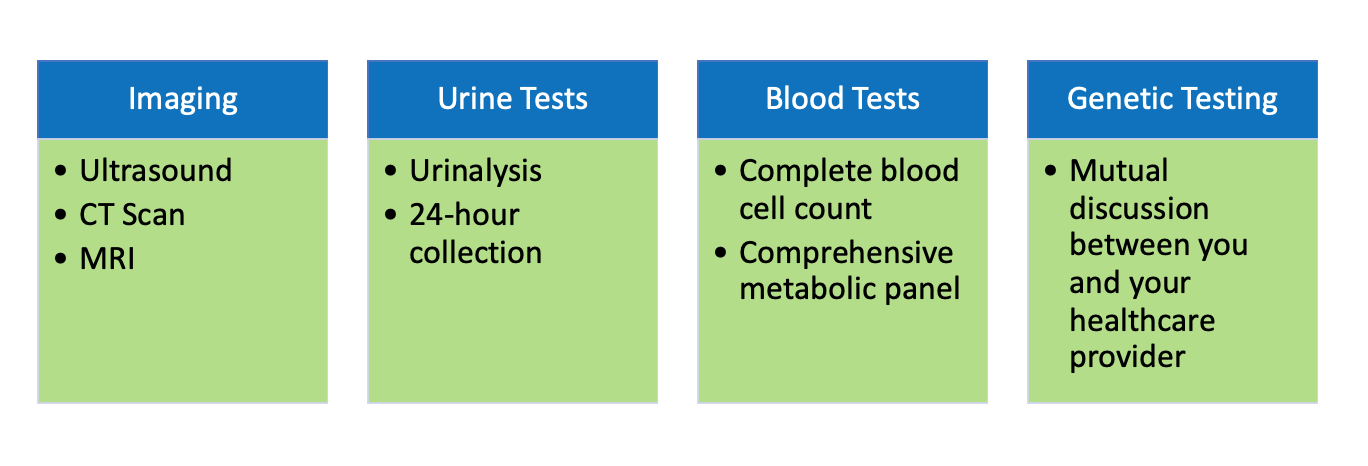

Your healthcare provider may also order the following diagnostic studies:

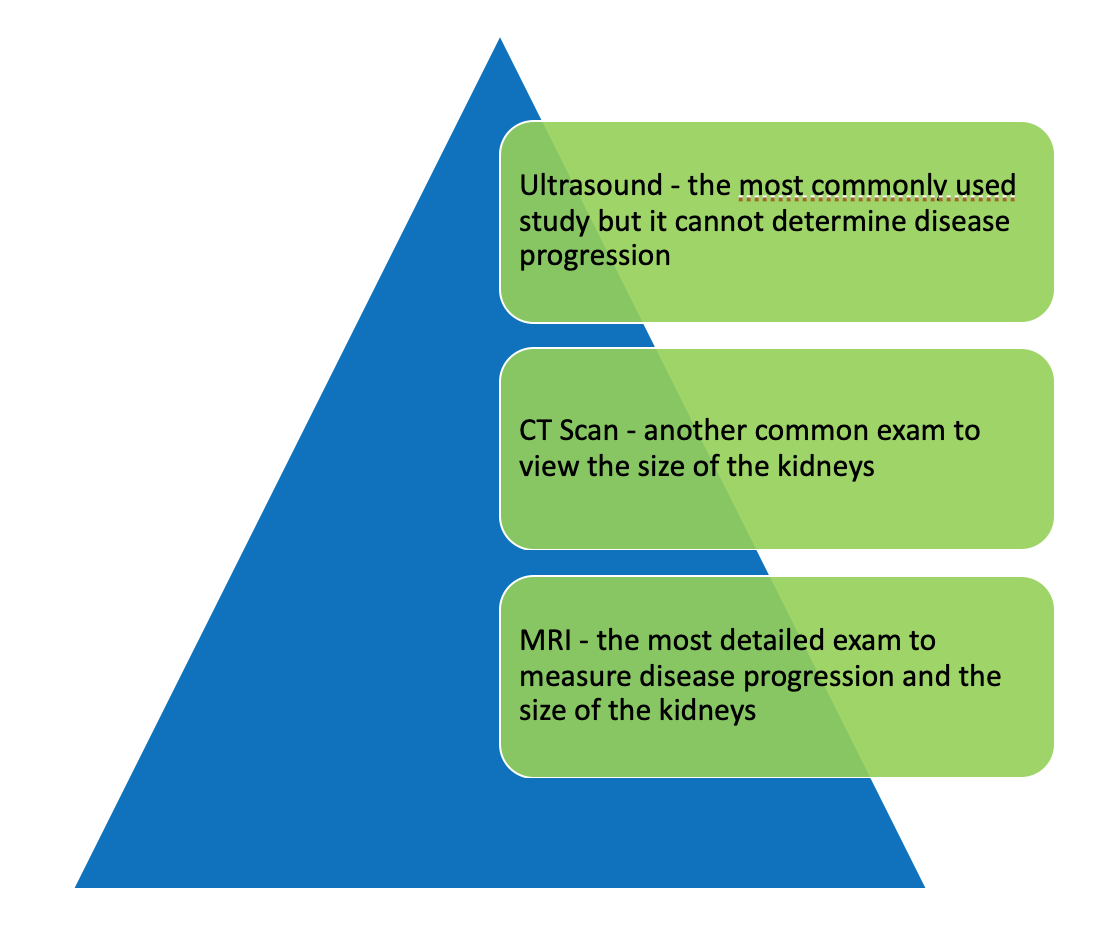

What do the imaging studies look for? Is one better than the other to make a diagnosis?

How is PKD treated? What lifestyle changes can I make?

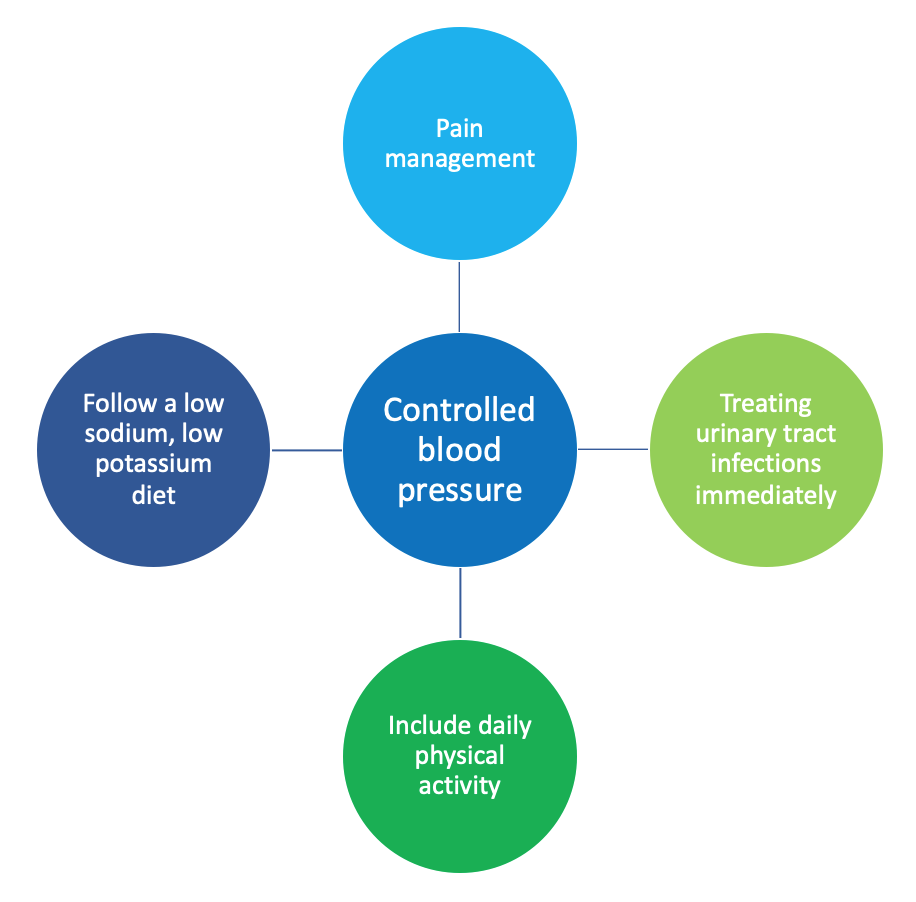

It will be important to have a nephrologist (kidney specialist) be a part of your healthcare team. Management of PKD should focus on controlling blood pressure and quickly treating any related complications you may have. Together, you and your healthcare team will develop an individualized care plan. There are various ways to manage the disease progress:

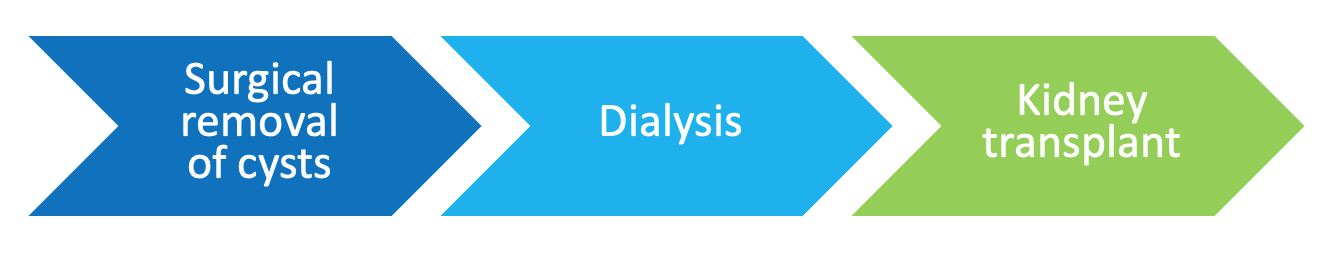

Even with close monitoring, managing your PKD may require more aggressive interventions. Talking with your healthcare provider will be important to determine next steps in treatment. These could include:

Is there a cure for PKD?

There is no cure for PKD, but a new treatment is available that has been shown to slow the progression of ADPKD to kidney failure. For more information, click here. Awareness, close monitoring and managing the symptoms will be most important to maintaining your health.

Are there complications to this disease?

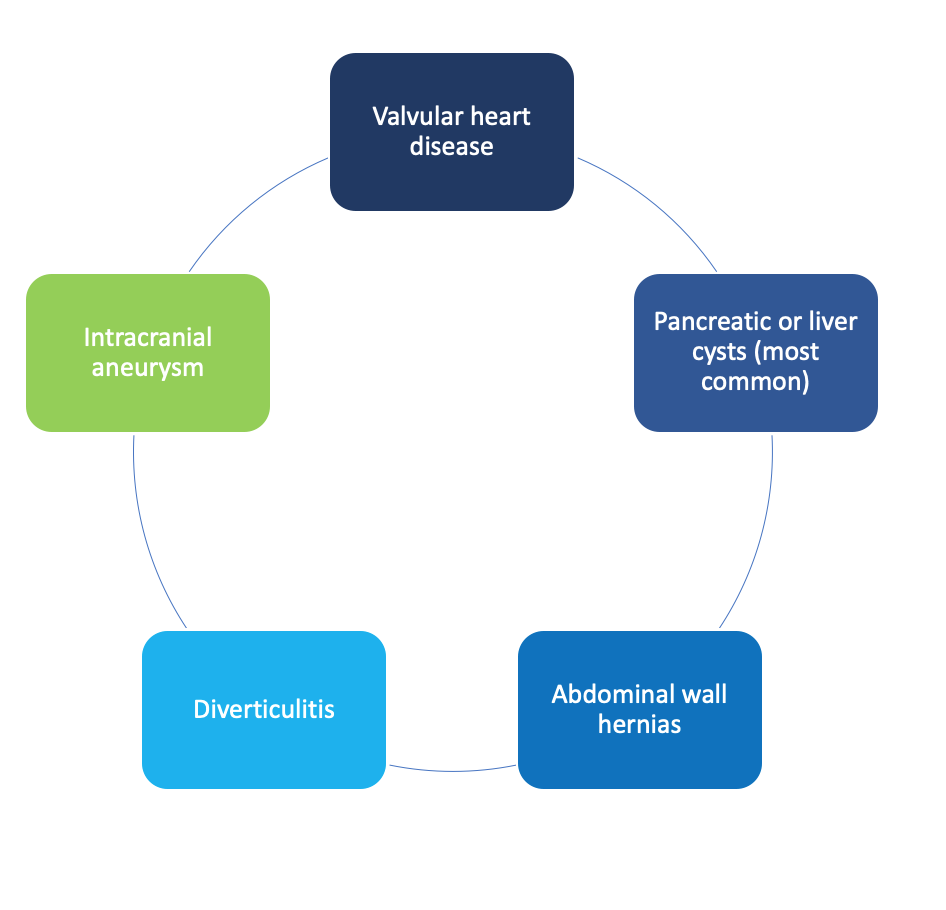

PKD has multiple complications that need to be monitored by your healthcare provider.

Complications to the kidney may include:

Other body systems that are affected include the heart, pancreas, liver, stomach, intestines, and brain and may lead to:

Additional Resources:

- AAKP Pocket Guide on Thinking about Genetics and Kidney Disease (Download)

- PKD Foundation