Myles Wolf, MD, MMSc for the HiLo Steering Committee

What is the best blood level of phosphate for people with kidney failure on dialysis?

An Update on the HiLo Trial

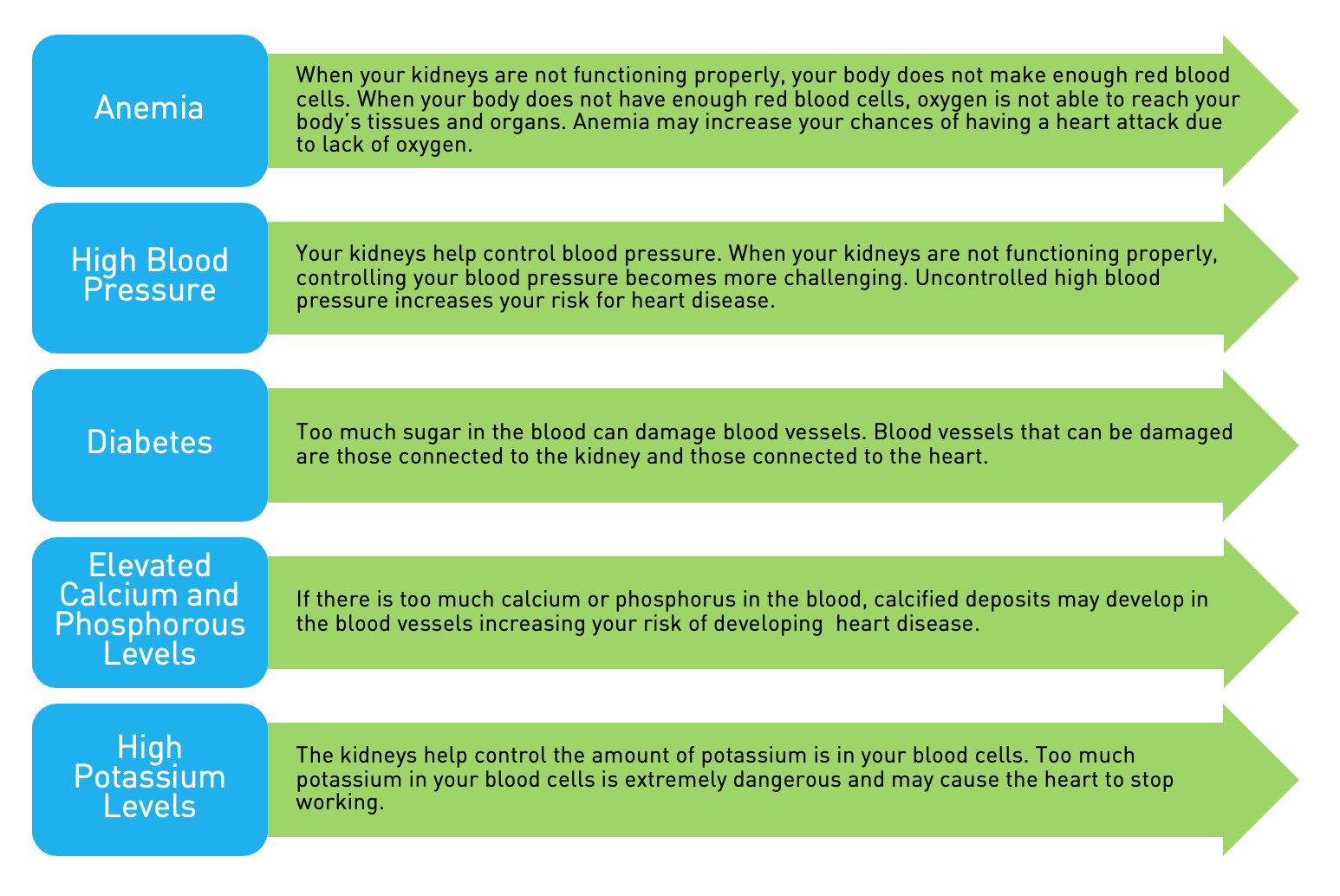

Hyperphosphatemia, defined as having too much phosphate in the blood, is a common problem in kidney patients receiving dialysis. Treating hyperphosphatemia can be time consuming and often frustrating for patients, families, dietitians, and nephrologists alike because of the burden of managing this condition. Common management of hyperphosphatemia requires patients to remember to take many phosphate binders pills multiple times per day before each meal, day after day, and to significantly restrict dietary choices. It is tough!

Given how challenging it can be for dialysis patients to control their phosphate levels, it is worth asking, what is the basis for how we treat hyperphosphatemia? From dietary counseling to phosphate binder choices to the serum phosphate targets we aim to achieve, observational studies mostly guide physician recommendations for treatment. These studies suggest that higher blood levels of phosphate are worse for dialysis patients when it comes to cardiovascular disease and survival. Is this a strong basis for how we treat?

Unfortunately, the short answer is no. Observational studies are not the most reliable type of study. As the name suggests, observational studies passively observe the outcomes of patients who get one treatment or another. Researchers use complicated analytical and statistical tools to try to distill a given treatment’s effects from all other factors that influence patients’ outcomes. It can be difficult for researchers to determine if a difference in one group’s outcome is caused by a given treatment or by other factors that were also different between the groups.

When deciding if one treatment approach is better than another, the most reliable study type is the randomized clinical trial. In randomized clinical trials, patients consent to participate and are randomly assigned to one or another treatment being compared in a given study. If observational studies are passive, randomized clinical trials are proactive.

When a large number of patients are included in a randomized clinical trial, randomization creates a balance between the two groups in their characteristics at the start of the study. For example, the average age, gender mix, rates

of diabetes, serum phosphate, and all other variables will usually be equal between the two groups. This is important because it means any differences in future outcomes between the groups are due to the treatment under study and are not related to other factors; for example, one group being healthier than the other at the start of the study.

Why do we rely on observational studies when randomized clinical trials provide much stronger evidence to determine whether one treatment is superior to another? Randomized clinical trials are labor intensive and can be extremely expensive. There are simply too many unknown clinical questions to answer with a dedicated randomized clinical trial. This is true in the area of dialysis, where we have many open questions and few randomized clinical trials.

To address this limitation, a new type of randomized clinical trial, called a pragmatic clinical trial, is being used increasingly.

Pragmatic clinical trials are conducted by patients and their health care teams within day-to-day clinical practice. Pragmatic clinical trials aim to be cost-effective. If we can make clinical trials less expensive, more of them can be done. Pragmatic clinical trials aim to be as inclusive as possible, and only a few criteria limit which individual patients can participate. The main goal of pragmatic clinical trials is to generate real-world answers to real-world clinical questions. The answers can be readily incorporated into clinical practice after the study ends and the results are known. Many of these characteristics differentiate pragmatic clinical trials from usual clinical trials. Usual clinical trials are administered by a separate group of dedicated research study staff, often include only a subset of patients who meet specific criteria, and usually involve extra study visits and extra data collection. Sometimes, these trials’ results don’t materialize when they are moved back into real-world practice because they were done in such a specialized way.

This is where the HiLo study comes in (https://hilostudy.org). HiLo is a pragmatic randomized clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that aims to address an important, unanswered question about the management of hyperphosphatemia in patients receiving dialysis. HiLo is testing whether aiming for a higher serum phosphate (6.5 mg/dl or higher) or a lower serum phosphate (less than 5.5 mg/dl) will improve survival and lower hospitalization rates for dialysis patients.

Initially, HiLo was designed as a cluster-randomized trial. This means that dialysis facilities were randomly assigned to either the Hi or Lo group. Practically speaking, patients who consented to participate in HiLo were asked to adhere to the serum phosphate target to which all consenting participants in their dialysis facility were assigned. HiLo started recruiting facilities and patients in March of 2020 and to date, recruited 555 patients from 30 DaVita dialysis facilities.

Upon reviewing the characteristics of the first 555 patients who joined HiLo, the HiLo Steering Committee observed that patients enrolled in the Hi group were, on average, younger and had higher serum phosphate levels when they entered the study compared to patients who enrolled in the Lo group. This could have been due to chance, but we worried that patients who historically struggled to keep their phosphate lower were more likely to agree to participate in HiLo if they were dialyzing in a facility that was assigned to the Hi group. Likewise, we worried that patients who historically have had lower serum phosphate levels were more likely to enroll in HiLo if it meant that they would be asked to be in the Lo group. Whatever the cause, the imbalances we observed could “bias” the final results of HiLo and limit the conclusions we would be able to make in the future when the trial would have been completed.

To prevent this potential problem, the study team spent the last year modifying the design of HiLo from a cluster-randomized to an individual-level randomized trial. This means that instead of randomizing whole dialysis units as we did initially, we are now randomizing individual patients one by one to either the Hi or Lo groups. Everything else about HiLo remains unchanged. We still aim to recruit over 4,000 dialysis patients. We are still comparing serum phosphate targets of less than 5.5 to at least 6.5 mg/dl. We are still comparing the effects of the Hi versus the Lo targets on hospitalization rates and survival. While making this significant update, we have encouraged and welcomed all participants who have already enrolled in HiLo to remain in the study.

In March 2022, the study resumed enrollment. While still early, we are encouraged by patients’ initial willingness to participate. We hope that we will be able to replicate our previous successful enrollment. In the initial phase of the study,

approximately 51.4 percent of dialysis patients who were offered inclusion into the study agreed to participate.

Interested in learning more about the HiLo Study?

If you would like to learn more about HiLo, please visit our website at https://hilostudy.org/. If you are undergoing dialysis in a DaVita facility and would like your site to consider participating in HiLo, please let us know at HiLo@dm.duke.edu, and please discuss this with your dietitian and nephrologist. We welcome your participation!

Acknowledgments

The Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) recognizes and thanks members from the following organizations who are volunteering their time, energy, and expertise to help conduct the HiLo Study – National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIH/NIDDK); DaVita Clinical Research; Davita, Inc. Dietitians; Northwestern University; University of Pennsylvania; and the American Association of Kidney Patients’ Center for Patient Research and Education.

Myles Wolf, MD, MMSc, is the Charles Johnson, MD, Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Nephrology at the Duke University School of Medicine. Dr. Wolf conducts laboratory-based and patient-oriented research focused on calcium and phosphate homeostasis across the spectrum of kidney disease. Dr. Wolf is Principal Investigator of the HiLo trial, which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to the Duke Clinical Research Institute.